- Home

- Collins, Max Allan

Hush Money Page 2

Hush Money Read online

Page 2

“Why in God’s name are you telling me this?”

“Because you’re going to find out anyway. You’re going to know. When you get settled down in Grayson’s chair and start examining his records, and then in about a year when those roads we laid down start cracking up like plaster of Paris, you’re going to know what was going on all right.”

“And I’m going to have the makings of a large-scale political scandal. Not to mention possible indictments against members of the DiPreta family.”

“Not to mention that.”

“Well. Thank you for the nine holes, Joey.” Carl rose. “And thank you for the information.”

“Sit down, Carl,” Joey said, pulling him back down to the cart seat with some force, though his voice stayed friendly and pleasant. “I’ll get you another beer.”

“I haven’t finished this one and I’m not about to. Let go of my arm.”

“Listen to me. All we want of you is silence. We will have no dealings with you whatsoever during your term of office, other than this one instance. My family is legitimate these days. This stuff with Grayson all took place back four, five years ago when Papa was still alive. My brothers and me are moving the DiPreta concerns into aboveboard areas completely.”

Carl said nothing.

“Look. The publicity alone could kill us. And like you said, it’s possible indictments could come out of it, and if indictments’re possible, so are prison terms, for Christ’s sake, and more investigations. So all we’re asking of you is this: Just look the other way. You’d be surprised how much it can pay, doing nothing. That’s what they call a deal like this: something for nothing.”

“It’s also called a payoff. It’s called paying hush money, Joey, cover-up money.”

“You can call it whatever you want.”

“How much, Joey? How much are the DiPretas willing to pay to hush me up?”

“You’re a wealthy man, Carl. You’re a banker. Your wife has money—her family does, I mean. Land holdings. It would take a lot to impress you.”

“Yes, it would.”

“I want you to keep in mind that an investigation would bring out your own contacts with the DiPreta family. We’ve been seen together this afternoon, for one thing, you and me. And those yearly Las Vegas junkets, on the last of which you and me were seen together . . .”

“You’re really reaching, Joey. Tell me, how much to cover it up? What’s the offer I can’t refuse?”

Joey leaned close and whispered with great melodramatic effect: “Fifty. Thousand. Dollars.”

Carl was silent for a moment. “That’s a lot of money. Could have been more, but it’s a lot of money.”

“A very lot, Carl. Especially when the IRS doesn’t have to know about it.”

“Let me ask you something, Joey.”

“Sure, Carl. Anything.”

“Where do we stand on our golf scores?”

“What? What are you . . .”

“Humor me. How many strokes down am I right now?”

“Well, uh, one stroke, Carl. I’m leading you by one, you know that.”

“Good. That way you’re going to be able to quit while you’re ahead, Joey. Because this game is over.”

Carl got up and out of the cart and began walking away.

“Carl!”

Without toning, Carl said, “Thank you for an interesting afternoon, Mr. DiPreta.”

“Carl, today you were offered money. Tomorrow it could be . . . something else. Something unpleasant.”

Carl kept walking.

Joey hopped out of the cart and said, almost shouting, “You know that term you used, Carl—hush money? That’s a good term, hush money. I like that. There’s two different kinds of hush money, you know—the kind you pay to a guy so he’ll keep quiet and the kind you pay to have a guy made quiet. Permanently quiet.”

Carl felt the heat rising to his face. Unable to contain his anger any longer, he whirled around, ready to deliver one final verbal burst, pointing his finger at Joey DiPreta like a gun.

And Joey DiPreta doubled over, as if shot, as if somehow a metaphysical bullet had been fired from the finger Carl was pointing; or at least that was Carl’s immediate impression.

Within a split second the sound of the high-power rifle fire caught up with the .460 Magnum missile that had passed through Joey DiPreta like a cheap Mexican dinner, tossing him in the air and knocking him off the mound and out of sight before Carl really understood what he’d just witnessed; before he really understood that he’d just seen a high-power bullet bore through a man and cut him literally in two and lift him up and send him tumbling lifelessly off the hillock.

Carl drew back the pointing finger and hit the deck, finally, rolled off the hill himself, to get out of the line of any further fire.

But there was none.

The assassin had hit his mark and fled, satisfied with his score for the afternoon, and why not? As one of Des Moines’ finest would later caustically point out, it isn’t every day somebody shoots a hole in one.

2

HIS NAME was Steven Bruce McCracken, but nobody called him any of those names. His friends called him Mac. His sister called him Stevie. His mother, when she was alive, called him Steve. His father, when he was alive, called him Butch. His crew had called him Sarge. The VC had called him a lot of things.

His reputation, it was said, was considerable among the Vietcong. That was what he’d heard from ARVN personnel, who themselves seemed a little in awe of him. To his own way of thinking, he’d never done anything so out of the ordinary; he was just one of many gunners, just another crew chief doing his job. As crew chief one of his responsibilities was to provide cover fire as men (usually wounded, since the bulk of his missions were Medivacs) were hustled aboard the helicopter. He would stand in the doorway, or outside of it, firing his contraband Thompson submachine gun (which he’d latched onto early in the game, picking it off a Cong corpse) and shouting obscenities in three languages at the usually unseen enemy, unflinching as return fire was sent his way, as if daring those gooks to hit him. Personally, he didn’t see how any of that could build him any special reputation among the enemy or anyone else. He always suspected those damn ARVN were putting him on about it—he had trouble understanding them half the time anyway, his Vietnamese lingo consisting mostly of bar talk and their English being no better—but later G-2 had confirmed that he did indeed have a name in Charlie’s camp. He supposed his appearance must’ve had something to do with whatever reputation he may have had. He stood out among the Americans, who, to the gooks, all looked alike, and he made a bigger target than most, which must’ve been frustrating as hell to the little bastards, missing a target so big. He was six-two and powerfully built—his body strung with holstered handguns and belts of ammunition and hand grenades—his white-blond hair and white-blond mustache (a slight, military-trim mustache that still managed a gunfighter’s droop on either side), showing up vividly against his deeply tanned skin.

His appearance today, a month out of service, was little different, even if he wasn’t wearing guns and ammo and grenades. True, the hair was already longer than the Marines would have liked, but other than that he looked much the same. His physical condition was outstanding; even his limp had lessened, seemed almost to have disappeared. A chunk of flesh along the inside of his right thigh had been blown away in the helicopter crash, just some fat and some not particularly valuable meat, leaving a hole six inches long by three inches wide, a purplish canyon that at its greatest depth was two inches. There was still some shrapnel in that hole, and pieces worked their way out now and then; he could feel them moving. Nothing to be worried about, really. He’d never look good in a bathing suit again, but what the hell? He was lucky. A few inches higher and he could’ve spent the rest of his life pissing through a tube and trying to remember what sex was like.

He’d been sole survivor of the crash. They’d been coming down into a clearing for a Medivac, and some fucking brush-huggin

g gook shot the hydraulic system out of the plane (they never called it a helicopter, always a plane) and made their landing premature and murderous. Coming down, they caught another shell, a big one, and at hover level the plane blew up and killed most of the men they’d been coming to save. He himself had been the only one on the scene who got off with relatively light injuries. The pilot lasted an hour, died just minutes before another plane came in to pick up survivors, which was him and two badly wounded ARVNs, one of them a lieutenant who died on the way back.

He had learned at the beginning not to form too close a friendship with any of his fellow crew members, because he’d had a whole goddamn crew shot from under him the first goddamn month. The damn mortality rate was just too fucking high for friendship.

But sometimes you can’t avoid it.

The pilot had been a friend. A friend he’d talked with and laughed with. A friend he’d gone on R and R with in Bangkok. A friend he’d shared smokes and booze and women with. A friend he’d held in his arms while a sucking chest wound took care of the future.

His own wound, the wound in his thigh, was nothing. Nothing compared to the wound left by the loss of his friend. Trauma, it’s called. At the hospital the powers that be decided he needed some visits with the staff psychiatrist, and by the time he was patched up again, mentally and physically, he was told that because of the trauma of losing the pilot and rest of the crew, because of that and his shot up leg, he was being sent home.

That had been fine with him at the time, but soon the trauma had faded, as far as he was concerned, and the leg felt better, and he demanded to be sent back; he’d re-upped specifically because he liked combat. But barely into his first tour of his reenlistment, he was stuck state-side. He was told he would not be sent back to Vietnam, because no one was being sent back: the gradual withdrawal of troops was under way, with the Marines among the first in line to leave.

He had no regrets about Vietnam, other than not getting his fill of it. He would’ve liked to have had another crack at the gooks; losing another crew had only made him more eager to wade in and fight. But now, finally, he was glad to be out of the Corps. His last two years and some months had been spent at glorious Quantico, Virginia, which was the sort of base that made Vietnam seem like a pleasant memory. State-side duty bored the ass off him; he preferred the war: that was where a soldier was meant to be, goddamn it, and besides, the pay was better. Sometimes he wished he had signed on as a mercenary, with Air America, instead of reenlisting in the Marines. As a mercenary he could’ve picked up a minimum of twelve thousand a year and be more than a damn toy soldier, playing damn war-games in the backwoods of Virginny.

But now that he was a civilian again—on the surface, anyway—he was glad he hadn’t gone the Air America route. He might have been killed as a mercenary, which was a risk he wouldn’t have minded taking before, and still didn’t, but not for money. The money a mercenary could make, which had once looked so attractive to him, seemed meaningless now. Dying wasn’t a disturbing concept to him, really; in fact sometimes it damn near appealed to him. What disturbed him was the thought of dying for no reason, without purpose. If he lost his life in pursuit of his private war, well, okay; at least he’d have died pursuing a worthwhile cause. You could argue the pros and cons of a Vietnam, but not this war, not his war. Anyone who knew the facts would agree—even the damn knee-jerk liberals, he’d wager.

Since parting company with Uncle Sugar, he’d been living alone in an apartment but spending some time with his sister and her small daughter. He didn’t have a job, or, rather, he didn’t have an employer. He told his sister he was planning to go to college starting second semester and actually had filled out applications for Drake, Simpson, and a couple of two-year schools in the area. Hell, he might even attend one of them, when his war was over; he had GI, he had it coming.

Not that he was thinking that far ahead. That was a fairy-tale happy ending, off in the fuzzy and distant future of a month from now, and he wasn’t thinking any further ahead than the days his war would last. Yes, days. With a war as limited as this one, a few days should be enough, considering no further reconnaissance would be necessary, to seek out and destroy the enemy. He’d been over and over the legacy of tapes, documents, committing them to memory, all but word for word, and he now knew the patterns, the lifestyle of the DiPreta family like he knew his own. A few days of ambush, of psychological warfare, and the score would be settled, the war would be won. He might even survive to go to college and become a useful member of society as his sister wanted. Who could say.

It was 4:47 p.m. when he arrived at the two-story white clapboard house, the basement of which was his apartment. The neighborhood was middle to lower-middle class, the house located on East Walnut between East 14th and 15th streets, two main drags cutting through Des Moines, 14th a one-way south, 15th a one-way north. His apartment’s location was a strategically good one. Fourteenth and 15th provided access to any place in the city, with the east/ west freeway, 235, a few blocks north; and he was within walking distance of the core of the DiPreta family’s most blatantly corrupt activities. A short walk west on Walnut (he would have to circle the massive, impressively beautiful Capitol building, its golden dome shining even on a dull, overcast afternoon like this one) and he’d find the so-called East Side, the rundown collection of secondhand stores, seedy bars, garish nightclubs, greasy spoons and porno movie houses that crowded the capitol steps like a protest rally. The occasional wholly reputable business concern seemed out of place in this ever-deteriorating neighborhood, as if put there by accident, or as a practical joke. At one time the East Side had been the hub of Des Moines, the business district, the center of everything; now it was the center of nothing, except of some of the more squalid activities in the capital city.

Location wasn’t the only nice thing about his living quarters; nicer yet was the privacy. He had his own entrance around back, four little cement steps leading down to the doorway. The apartment was one large room that took up all of the basement except for a walled-off laundry room, which he was free to use. He also had his own bathroom with toilet and shower, though he did have to go through the laundry room to get to it. Otherwise his apartment was absolutely private and he had no one bothering him; he saw the Parkers (the family he rented from) hardly at all. He had a refrigerator, a stove, and a formica-top table that took up one corner of the room as a make-do kitchenette. A day bed that in its couch identity was a dark green went well with the light green-painted cement walls. There was also an empty bookcase he hadn’t gotten around to filling yet, though some gun magazines and Penthouses were stacked on the bottom shelf (he’d given up Playboy while in Nam, as he didn’t care for its political slant) and a big double-door pine wardrobe for his clothes and such, which he kept locked.

The wardrobe was where he stowed the Weatherby, which he’d brought into the house carried casually under and over his arm. It was zipped up in a tan-and-black vinyl pouch, with foam padding and fleece lining, and he’d made no pretense about what he was carrying. He’d already explained to the Parkers that shooting was his hobby. Luckily, Mr. Parker was not a hunter or a gun buff, or he might’ve asked embarrassing questions. Someone who knew what he was talking about might have looked at the Weatherby and asked, “What you planning to shoot, lad? Big game?”

And he would’ve had to say, “That’s exactly right”

He laid the Weatherby Mark V in the bottom of the wardrobe, alongside the rest of the small but substantial arsenal he’d assembled for his war: a Browning 9-millimeter automatic with checkered walnut grips, blue finish, fixed sights, and thirteen-shot magazine, in brown leather shoulder holster rig; a Colt Python revolver, blue, .357 Magnum with four-inch barrel, wide hammer spur and adjustable rear sight, in black leather hip holster; a Thompson submachine gun, .45 caliber, black metal, brown wood; boxes of the appropriate ammunition; and half a dozen pineapple-type hand grenades, which he’d made himself, buying empty shell casings, fillin

g them with gunpowder, providing primers.

He closed the wardrobe but left it unlocked.

He felt fine. Not jumpy at all. He sniffed under his arms. Nothing, not a scent; this afternoon had been literally no sweat. That was good to know, after some years away from actual combat. Good to know he hadn’t lost his edge. And that the helicopter crash hadn’t left him squeamish: that was good to know, too. Very.

But he took a shower anyway. The hot needles of water melted him; he dialed the faucet tight, so that the water pressure would stay as high as possible. If he told himself there was no tension in him, he’d be lying, he knew. He needed to relax, unwind. He’d stayed cool today, yes, but nobody stays that cool.

The phone rang and he cut his shower short, running bare-ass out to answer it, hopping from throw rug to throw rug to avoid the cold cement of a basement floor that was otherwise as naked as he was.

“Yes?” he said.

“Stevie, where’ve you been? I been trying to get you.”

It was his sister, Diane. She was a year or two older than he, around thirty or so, but she played the older sister act to the hilt. It was even worse now, with their parents dead.

“I was out, Di.”

“I won’t ask where. I’m not going to pry.”

“Good, Di.”

“Well, I just thought you’d maybe like to come over tonight for supper, that’s all. I came home over lunch hour and put a casserole in, and it’ll be too much for just Joni and me.”

Joni was her six-year-old daughter. Diane was divorced, but she hadn’t gotten out of the habit of cooking for a family, and consequently he’d been eating at her place several nights a week this last month. Which was fine, as his specialty was canned soup and TV dinners.

Scratch Fever

Scratch Fever Stolen Away

Stolen Away The Wrong Quarry (Hard Case Crime)

The Wrong Quarry (Hard Case Crime) Quarry

Quarry Hard Case Crime: Deadly Beloved

Hard Case Crime: Deadly Beloved Hush Money

Hush Money The Million-Dollar Wound

The Million-Dollar Wound Mourn The Living

Mourn The Living True Crime

True Crime Hard Cash

Hard Cash Triple Play: A Nathan Heller Casebook

Triple Play: A Nathan Heller Casebook Hard Case Crime: The First Quarry

Hard Case Crime: The First Quarry Spree

Spree Chicago Lightning : The Collected Nathan Heller Short Stories

Chicago Lightning : The Collected Nathan Heller Short Stories Fly Paper

Fly Paper Seduction of the Innocent (Hard Case Crime)

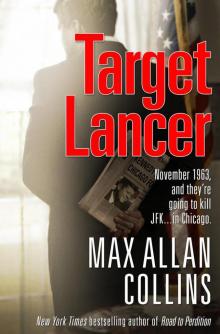

Seduction of the Innocent (Hard Case Crime) Target Lancer

Target Lancer