- Home

- Collins, Max Allan

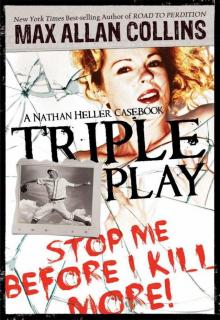

Triple Play: A Nathan Heller Casebook

Triple Play: A Nathan Heller Casebook Read online

TRIPLE PLAY

A Nathan Heller Casebook

The Memoirs of Nathan Heller

True Detective

True Crime

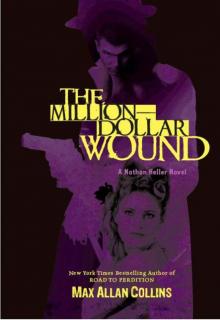

The Million-Dollar Wound

Neon Mirage

Stolen Away

Carnal Hours

Blood and Thunder

Damned in Paradise

Flying Blind

Majic Man

Angel in Black

Chicago Confidential

Bye Bye Baby

Chicago Lightning (short stories)

Triple Play (novellas)

TRIPLE PLAY

A Nathan Heller Casebook

MAX ALLAN COLLINS

This book is a work of fiction. Names, characters, businesses, organizations, places, events, and incidents either are the product of the author’s imagination or are used fictitiously.

Dying in the Post-War World copyright © 1991 Max Allan Collins

Kisses of Death copyright © 2001 Max Allan Collins

Strike Zone copyright © 2001 Max Allan Collins

All rights reserved

No part of this book may be reproduced, or stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without express written permission of the publisher.

Published by Thomas & Mercer

P.O. Box 400818

Las Vegas, NV 89140

ISBN: 978-1-61218-092-2

A fedora tip to George Hagenauer—

whose work on these three Heller cases

deserves special thanks

Although the historical incidents in these novellas are portrayed more or less accurately (as much as the passage of time and contradictory source material will allow), fact, speculation, and fiction are freely mixed here; historical personages exist side by side with composite characters and wholly fictional ones—all of whom act and speak at the author’s whim.

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Introduction

Dying In The Post-War World

Chapter 1

Chapter 2

Chapter 3

Chapter 4

Chapter 5

Chapter 6

Chapter 7

Chapter 8

Chapter 9

Chapter 10

Chapter 11

Chapter 12

Chapter 13

Chapter 14

Chapter 15

Chapter 16

Chapter 17

Chapter 18

Chapter 19

Chapter 20

Chapter 21

Kisses of Death

Chapter 1

Chapter 2

Chapter 3

Chapter 4

Chapter 5

Chapter 6

Chapter 7

Chapter 8

Strike Zone

Chapter 1

Chapter 2

Chapter 3

Chapter 4

Chapter 5

I Owe Them One

About the Author

TRIPLE PLAY

AN INTRODUCTION

BY MAX ALLAN COLLINS

Is there a difference between a novella and a novelette? Damned if I know.

But I do know that both seem to happen around the point where the very long short story meets the very short novel. It’s a form that was once quite popular, often showcased by such major magazines as The Saturday Evening Post, Redbook, Cosmopolitan, Liberty, and Collier’s. Even in the 1960s and early ’70s, the classier men’s adventure magazines—and being one of the classier men’s adventure magazines, of course, didn’t really make you very classy—would reserve the last section of their periodicals for novelettes, usually by famous mystery writers.

For many years, the great Rex Stout would write one Nero Wolfe novel and one Wolfe novelette a year, the latter for various “slick” magazine markets. When he’d done three of the short novels, he would collect them into a book; these novella collections bore such titles as Triple Jeopardy, Three Men Out, Trouble in Triplicate, and Curtains for Three. Stout is obviously very at home in the 20,000-word form, and the A&E Nero Wolfe TV series of a few years back often used the novellas as the basis for scripts. Stout lived to a ripe old age, leaving us a wealth of wonderful stories, but he also lived long enough to see the market for novellas dry up, and he, Nero Wolfe, and Archie Goodwin spent the last ten years of their collective career only in novels.

Mickey Spillane—during his self-imposed hiatus from writing Mike Hammer yarns (1952–1962) at the peak of his popularity—kept his hand in by writing 20,000-word tales for men’s magazine the likes of Cavalier and Saga. The pulps were largely gone in the ’50s and ’60s, Black Mask—where Dashiell Hammett and Raymond Chandler cut their teeth—was already just a memory; but Black Mask’s successor, Manhunt, launched itself in 1953 with a four-part serialized Spillane mininovel. During its decade-and-a-half run, Manhunt often showcased short novels by Richard S. Prather, Brett Halliday, Cornell Woolrich, Ed McBain, Ross MacDonald, Charles Williams, and many other major writers of noir fiction of the 1950s and ’60s.

Manhunt wasn’t alone, getting competition from Mike Shayne Mystery Magazine and the still-going (if more genteel) Ellery Queen’s Mystery Magazine, as well as a succession of short-lived digest-sized pulps wearing the names of writers (Rex Stout), famous fictional detectives (The Saint), and even TV series (77 Sunset Strip).

Many of the novellas published by Manhunt and its rivals wound up expanded into novels, sometimes appearing in hardcover but more often as paperbacks. Mystery novels of the mid-twentieth century were often short by today’s standards—40,000 to 50,000 words. A number of paperback publishers followed the lead of Fawcett Publications’ Gold Medal Books in putting out tough, sexy, hardboiled novels about PIs, crooks, cops, and (following the lead of James M. Cain’s Postman Always Rings Twice) hapless ordinary guys caught up in crime and lust.

The mystery digests, and paperback houses like Gold Medal Books, were filling the void left by the pulps of the Black Mask era. Gold Medal was specifically formed to take advantage of the mostly male, post–World War II market unveiled by New American Library’s enormously successful paperback reprints of I, the Jury and Mickey Spillane’s other early Mike Hammer novels.

Much like Elvis Presley with rock ’n’ roll, Spillane broke down barriers on sex and violence in popular culture that caused reverberations still felt today, and the sexy covers of the Hammer reprints set the standard and tone for Gold Medal and other publishers. In his hardcover mysteries, Spillane also wrote fairly short yarns—more like 60,000 words on average—but still the kind of swift, startling read that really caught and held a reader’s attention.

As the years have passed, however, the short novel—even the 40,000–50,000 word variety—has become an endangered species. Occasionally a magazine like Ellery Queen will publish a longer story, as do anthologies of original material. Still, when I came along with my Nate Heller character in the early ’80s, the demand for novelettes was right in there with the call for buggy whips and codpieces.

At first, writing short stories themselves seemed like a waste of time to me. You had to create stories “on spec,” that is, just write the damn things, send them in to one of the handful of markets, and pray for acceptance. My agent wouldn’t even bother with marketing short stories (still doesn’t). With a novel, on the other hand, I could write a proposal and perhaps a sample chapter or two, and land a contract—sometimes a two- or even three-book contract. It still works that way more than a decade into the twenty-first century.

But in the ’80s and ’90s, original material antholo

gies became fashionable (and are still around, though starting to look like potential buggy whips and/or codpieces), and now and then I would be invited into a collection of original stories. When you’re asked to the party, you have to really misbehave to get tossed out. I’ve never been invited to contribute a story to such a collection only to be rejected. As an editor of around ten anthologies of that ilk, I believe I only rejected one story, and perhaps asked for rewrites on half a dozen (of 150 or more stories). So as bets go in the writing game, an invite from an anthologist is a safe one.

Still, requests for novellas are rare. So far in my career—and Nate Heller’s—I’ve only been asked to write short novels on three occasions. Two collections of my Heller short stories, by separate publishers, needed a new story to attract readers who’d already seen those previously published tales. In both cases, the editors requested a novella to both plump out the volume and to further make a purchase attractive to readers who already had some, or maybe all, of the rest of the stories. (Both of those “casebook” collections are out of print, and this volume—and Chicago Lightning, another short story collection from AmazonEncore—take their place.)

The idea of a short Heller novel appealed to me on any number of levels. The novels always take on major crimes and are massive undertakings of research and narrative. The short stories allow me to do chamber pieces, tackling small, un-famous crimes that would find Heller behaving more like a day-to-day detective, getting away from the admittedly ridiculous notion that every single case of his involves a world-famous crime.

A short novel, on the other hand, splits the difference. It allows Heller and me to take on a case that involves a famous crime or famous people but that doesn’t quite qualify for the full-scale, 100,000-word treatment.

In “Dying in the Post-War World,” I was able to take on the William Heirens “lipstick killer” case, which was well known but not really complex enough to justify novel-length treatment. This first Heller novella was approached as if I were writing a Gold Medal paperback back in 1963, relishing the opportunity to take my detective into a format I’d grown up reading and loving.

One of the most interesting things about writing that particular novella was hearing by mail from the still-incarcerated William Heirens. For several years I received Christmas cards from him, from prison. What did the convicted lipstick killer think of the story? Well, he commended me for being fair, but said he “disagreed” with certain aspects of my take on the crimes. Which aspects, I think, should be clear to you once you’ve read the novella.

The circumstances of “Kisses of Death” are unusual. A small Chicago audio firm had been doing abridged versions of the Heller novels, with me reading. They wanted to promote these audiobooks at the upcoming 1996 American Booksellers Association convention in Chicago. They wondered if I could write a Heller novella set at the ABA, and then we’d record it, and give it away at their booth.

While the ABA does figure into the story, “Kisses of Death” is mostly about Marilyn Monroe, who I knew had worked on her autobiography (not published till many years after her death) with legendary Chicago writer Ben Hecht of Front Page fame. I’d long wanted to get Hecht on stage in the Heller saga, and had always known Marilyn would enter, when I moved out of the ’30s and ’40s into the 1950s. But I needed a literary murder to tie it all together—the audiobook was designed to be given away at the ABA event, after all.

My longtime research associate, George Hagenauer, came through, with an incident involving prototypical beatnik poet/novelist, Maxwell Bodenheim. The Bodenheim case was exactly the kind of story suitable for a novella—too big for a short story, too small for a full-scale novel. Bodenheim also fit right in with Marilyn’s own ambitions and pretensions toward becoming an intellectual.

I wrote the story, recorded it (with my lovely wife Barbara reading the Marilyn Monroe lines), and we gave away a bunch of cassettes at that year’s ABA exhibition at Chicago’s McCormack Place. It did not appear in print until 2001 when it became the title story of the second Heller casebook.

In “Strike Zone,” I took advantage of a particularly peculiar crime—the murder of the most famous pinch hitter in history, who happened to be a midget—and also explored colorful baseball legend Bill Veeck. George Hagenauer had known Veeck quite well, which was a big plus. This novella, the shortest of the three collected here, was written at the request of Otto Penzler for a baseball crime/mystery anthology. Another author had dropped out, and Otto needed a long story to help reach the anthology’s overall required word count.

I was glad to help out, though I admitted to Otto—and will admit to you—that I am not a baseball fan. Few baseball references appear in the Heller memoirs (boxing is his sport of choice). My late father, Max A. Collins Sr., however, was one of the greatest fans of baseball (and sports in general) who ever lived, and I dedicate that story—and this book—to his memory.

—Max Allan Collins

February 2010

DYING IN THE POST-WAR WORLD

1

Life was pretty much perfect.

I had a brand-new brown-brick GI Bill bungalow in quietly suburban Lincolnwood; Peggy, my wife since December of last year, was ripely pregnant; I’d bribed a North Side car dealer into getting one of the first new Plymouths; and I’d just moved the A-1 Detective Agency into the prestigious old Rookery Building in the Loop.

True, business was a little slow—a good share of A-1’s trade, over the years, has been divorce work, and nobody was getting divorced right now. It was July of 1947, and former soldiers and their blushing brides were still fucking, not fighting, but that would come. I was patient. In the meantime, there were plenty of credit checks to run. People were spending dough, chasing after their post-war dreams.

Sunlight was filtering in through the sheer curtains of our little bedroom, teasing my beautiful wife into wakefulness. I was already up—it was a quarter to eight, and I tried to be in to work by nine (when you’re the boss, punctuality is optional). I was standing near the bed, snugging my tie, when Peg looked up at me through slits.

“I put the coffee on,” I said. “I can scramble you some eggs, if you like. Fancier than that, you’re on your own.”

“What time is it?” She sat up; the covers slid down the slope of her tummy. Her swollen breasts poked at the gathered top of her nightgown.

I told her the time, even though a clock was on the nightstand nearby.

She swallowed thickly. Blinked. Peg’s skin was pale, translucent; a faint trail of freckles decorated a pert nose. Her eyebrows were thick, her eyes big and violet. Without makeup, her dark brown curly locks a mess, seven months pregnant, first thing in the morning, she was gorgeous.

She, of course, didn’t think so. She had told me repeatedly, for the last two months—when her pregnancy had begun to make itself blatantly obvious—that she looked hideous and bloated. Less than ten years ago, she’d been an artist’s model; just a year ago, she’d been a smartly dressed young businesswoman. Now, she was a pregnant housewife, and not a happy one.

That was why I’d been making breakfast for the last several weeks.

Out in the hall, the phone rang.

“I’ll get it,” I said.

She nodded; she was sitting on the bed, easing her swollen feet into pink slippers, a task she was approaching with the care and precision of a bomb-squad guy removing a detonator.

I got it on the third ring. “This is Heller,” I said.

“Nate…this is Bob.”

I didn’t recognize the voice, but I recognized the tone: desperation, with some despair mixed in.

“Bob…?”

“Bob Keenan,” the tremulous voice said.

“Oh! Bob.” And I immediately wondered why Bob Keenan, who just a passing acquaintance, would be calling me at home, first thing in the morning. Keenan was a friend and client of an attorney I did work for, and I’d had lunch with both of them, at Binyon’s, around the corner from my old office on Van Buren,

perhaps four times over the past six months. That was the extent of it.

“I hate to bother you at home…but something…something awful’s happened. You’re the only person I could think of who can help me. Can you come, straightaway?”

“Bob, do you want to talk about this?”

“Not on the phone! Come right away. Please?”

That last word was a tortured cry for help.

I couldn’t turn him down. Whatever was up, this guy was hurting. Besides which, Keenan was well off—he was one of the top administrators at the Office of Price Administration. So there might be some dough in it.

Scratch Fever

Scratch Fever Stolen Away

Stolen Away The Wrong Quarry (Hard Case Crime)

The Wrong Quarry (Hard Case Crime) Quarry

Quarry Hard Case Crime: Deadly Beloved

Hard Case Crime: Deadly Beloved Hush Money

Hush Money The Million-Dollar Wound

The Million-Dollar Wound Mourn The Living

Mourn The Living True Crime

True Crime Hard Cash

Hard Cash Triple Play: A Nathan Heller Casebook

Triple Play: A Nathan Heller Casebook Hard Case Crime: The First Quarry

Hard Case Crime: The First Quarry Spree

Spree Chicago Lightning : The Collected Nathan Heller Short Stories

Chicago Lightning : The Collected Nathan Heller Short Stories Fly Paper

Fly Paper Seduction of the Innocent (Hard Case Crime)

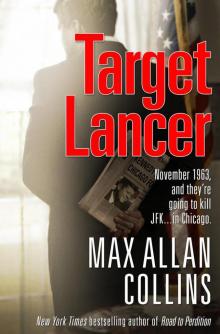

Seduction of the Innocent (Hard Case Crime) Target Lancer

Target Lancer