- Home

- Collins, Max Allan

Quarry Page 2

Quarry Read online

Page 2

“Clean liver, huh?”

“That shit can kill you,” I said, fanning her smoke out of my face. “But it’s your life, do what you want.”

“You like to play at being hard, don’t you.”

“You don’t seem to mind me hard.”

She grinned and reached a hand down and played with me but neither it nor I was having any.

So she gave up and a few seconds went by and she said, “I got some booze, you thirsty?”

I was thinking that one over when outside, sirens cut the air.

“What the hell was that?” she said.

“Sirens.”

“Yeah, that’s what I thought it was. Sounded like they went by here. Something happen at the airport, you suppose?”

“Somebody had a heart attack maybe.”

“Yeah. Ambulance, then, not police.”

“Who knows.”

“Yeah. Hey, should I build us some drinks or not?”

“I don’t think so.”

“Come on.”

“Look,” I said, “this has been pleasant, but I got no desire to do a number with your husband should he come back early or something. I’ll just put my trunks on and go swimming again, okay?”

“Aw, stick around.”

“No thanks.”

“Prick.”

I shrugged and got my trunks on and slid the glass door open. I strolled out to the pool and walked over to the diving board. Up on the board I bounced and looked across the grassy field toward the airport. It was all lit up, but no more than usual, and I couldn’t make out whether there were any ambulance or cop car lights up there. Not that it mattered. I dove in. The water was cold.

3

* * *

* * *

THE BEST PART of the meal was the skillet of mushrooms. The Chablis was okay, but I don’t know enough about wine to tell good from bad. But I do know mushrooms, I’ve gone picking them before, and know enough to take the sponge and leave the button top be. You never can tell about button top, unless you get commercial grown. Like these were. Big and round as half dollars and plump and juicy and fine.

The steak was just fair, being grainy like maybe it was injected with something to make it tender while it was still a cow, but you got to remember too that I was full on bread and salad and mushrooms before I even got to the steak. Finishing the wine seemed a good top priority, and the last of it was just trickling down my throat when the Broker and his wife walked past my table, neither one of them showing a trace of recognition.

Which made sense with the wife, since she never saw me before. She was an aristocratic-looking, icy ice-blonde of maybe thirty-five who probably came out of one of those exclusive girl’s schools with a name like a winter resort, where a nun or some other kind of old maid had taught her how to be a proper little glacier.

She was good-looking enough to make you wonder if Broker picked her like he would any front or maybe there was some sex or love in it somewhere.

A girl in a short-skirted barmaid outfit seated the Broker and his missus in a secluded corner where two wine-rack walls met. She took their drink order and then a kid in a rust-color puffy-sleeve cavalier shirt waited on them. The outfits fitted in with the glorified old English pub atmosphere of the place: high ceiling, rough wood, a central roaring fireplace (gas), and huge wrought-iron chandeliers above pouring out coppery semilight from candles (electric).

I poked at my steak and waited for Broker to make a move. He made an effort not to look my way. I stared at him. At his brown double-knit pinstripe suit. At his distinguished white hair. At the prissy expression under the wispy mustache.

He stood, excused himself with his wife, who didn’t seem to notice he was getting up to go. He was a tall man, six-two and well-built, but he walked like he was gelded.

I watched him go past me and round the fireplace and head toward the restrooms. I waited a minute or two—I was willing to play his game that far—and then went after him.

He was washing his hands. A guy was taking a leak and one of the crappers was occupied. I walked over to one of the urinals and got busy.

After a while everybody left, except Broker and me, and I joined him at the sinks. Broker stopped washing his hands, but he kept the water running.

“Well?” he said.

“Don’t ever try pulling anything like this on me again, Broker.”

“How did it go?”

“It went.”

“Did you get what he had?”

I looked at the Broker’s double-knit brown suit. He was wearing a blue shirt and a white tie and his cheeks were rosy. He was fifty and he looked forty and his face was long and fleshy without many lines.

“I got it,” I said.

Somebody came in and Broker started washing his hands again. I joined him. The guy did what he had to and left.

“Seems like when I work with you,” I said, “all my time’s spent in toilets.”

“Is that where you took care of him? In a restroom?”

“No. I walked him out to the runway and threw him in front of a Boeing.”

A little dark guy with a little dark son came in and stood at the urinals, like a big salt shaker and a smaller pepper. When they were done they seemed to want to wash their hands, but Broker and me had the sink concession, so the pair gave up quick and left.

“What are you upset about, Quarry?”

“Horse.”

“What are you talking about?”

“I’m talking about H, Broker. Smack. Heroin, horse, shit, horseshit!”

“Will you please keep your voice down?”

“Christ, Broker. That’s all I need is to get found with a bundle of that on me. I got enough fucking risk going for me as it is.”

“You disappoint me, Quarry.”

“I disappoint you.”

“You were told your man had a valuable package which did not belong to him. You weren’t told to examine the contents of the package.”

“It was a lump of snow in a plastic bag, Broker, it didn’t take a goddamn chemist to tell.”

“Since when are you so God almighty precautious? You complain of risk. Yet you use the same gun from job to job, don’t you? That would seem a dangerous habit to me.”

“That is one thing. This other today is something else.”

“I’m not going to stand here and argue with you, Quarry. My hands are getting puckered from washing.”

“Your hands are getting puckered. My ass is getting puckered! Look, I work one kind of thing, and I work it one kind of way, you know that better than anyone else, but what do you do? You bring me in for a half-ass deal like this one.”

“This was last minute, Quarry, I called you in for something else entirely, and . . .”

“I don’t like getting brought to town for one job and doing another. I don’t like playing courier with a load of H. You want to play with smack, get a pusher. And this humiliating people, I got no stomach for that. You got somebody who’s going to die, fine, I’ll be the means. You want strong-arm, get a goon.”

“Are you quite finished?”

“Don’t pull that pompous bullshit tone on me, Broker. I’ve known you too long. I know what you are.”

“If you don’t like working for me, Quarry, why don’t you just quit?”

“What? What did you say?”

“I said if you don’t like working for me you can always quit.”

“Now that tears it. Now that really fucking tears it.”

“What are you talking about?”

“You work for me, Broker, don’t forget that . . . I work for you like Richard Burton works for his agent.”

Broker sighed. “Where’s the stuff, Quarry?”

“Never do this to me again, Broker. Understand? Nothing else like this. Or you’re going to see the side of this business you don’t like seeing.”

“Where’s the stuff?”

“Do you get my meaning, Broker?”

“Yes. Where

’s the stuff?”

“Where’s my money?”

Broker turned off the faucet and wiped his hands on a paper towel. He took an envelope from his inside jacket pocket. He handed the envelope to me and I looked inside: three thousand in hundreds. I put the envelope in my inside pocket.

“I’m still at the Howard Johnson’s,” I said. “You come talk to me there. You know what room I’m in. I’m sick of using cans for my office.”

“What?”

“And don’t send anybody around to see me, Broker, or I’ll do bad things to them. You come. We got talking to do.”

“Don’t play with me, Quarry.”

“Who’s playing? Better zip up, Broker.”

“Quarry . . .”

I dried my hands and left.

4

* * *

* * *

I SUPPOSE AT this point I should be filling you in on my background and telling you how I got into such a specialized line of work. Don’t count on it. There are two things you won’t get from me and that’s details about my past and my real name. The closest you’ll get to a name is Quarry, which is an alias suggested by the Broker and I always kind of liked it, as aliases go. Or I did until I asked Broker why he suggested an offbeat name like that one and he chuckled and said, “Know what a quarry is, don’t you? It’s rock and it’s hollowed out.” Broker isn’t known for his sense of humor.

I will sketch in some of my background, in case you feel the need to try to understand me. I’m a veteran of the Vietnam fuckup, which was where I learned about the meaninglessness of life and death, though the point wasn’t really driven home until I arrived back in the states and found my wife shacked up with a guy named Williams who had a bungalow in La Mirada and a job in a garage. I was going to shoot the son of a bitch, but waited till I cooled down enough to think rationally. Then I went to his house where he was in his driveway on his back working under his car and kicked the jack out . . . once in a movie I heard death referred to as “the big crushout,” and for that poor bastard the phrase couldn’t have been more apropos. I didn’t shoot my wife, or drop a car on her either. I just divorced her. Or rather she divorced me.

Of course no court in the world would have touched me, a cuckolded serviceman fresh home from the fight. But no one wanted me for an overnight house guest either. I couldn’t find work, even though I was a fully qualified mechanic . . . and it wasn’t like there weren’t any openings. The garage where Williams worked could’ve used a man, that was for sure.

The only relative I had who would even look me in the face was my old man, who came out to L.A. to see me after I had my little marital problem. He told me not to come home, said I’d made my stepmother nervous even before I started murdering people and God only knew how I’d affect her now. I never did ask the old man which murders he was talking about, the dozen or so in Vietnam or the one in California.

Since I couldn’t go home to Ohio with my father, I just hung around L.A. for a month or so, spending my money as fast as I could, going to movies during the days and bars at night. That got old fast. California got old fast. It was where I was stationed before going overseas and was where I fell into the star-crossed romance that ended in marriage, among other things, with that brown-haired bitch whose face is fuzzy in my memory now.

I don’t know how the Broker got a line on me. Maybe it’s like pro football teams recruiting players; maybe Broker sends scouts around to bars to look for guys with faces full of no morality. Or maybe Broker and his people pay attention to certain of us who get back from service and have problems. I know mine was in the papers and got enough publicity to keep me from getting jobs when I applied. You know I never did figure out how everybody could be so goddamn back-patting sympathetic and still not be willing to risk giving me a job.

Everybody but Broker. He had a job for me. I don’t remember the conversation. I know it was elliptical. You don’t come right out and ask somebody if he’d like to kill people for money. Even Uncle Sugar is more subtle than that.

Anyway, Broker showed up one day at what could best be described as my fleabag one-room apartment in L.A. and somehow or other got across to me what he was talking about . . . that I could make top dollar continuing to do what I had just finished doing for peanuts and, in one case, for free. Killing people, that is.

I accepted without hesitation. My eager but unemotional “yes” must’ve nearly scared the Broker off. He told me later he was usually wary of a fast yes; he didn’t want anyone working with him who might be the type who drooled for a chance to shoot anything that breathed: madmen don’t make the world’s most reliable, efficient employees. But my lack of emotion counterbalanced any such fear Broker might’ve harbored, especially on top of the thorough researching he’d had done on me.

Why did I say yes? Why did I say yes so quickly? I guess I was hungry for the chance to do something, anything, especially a high-paying something or anything. Though I’d learned in Nam to accept life and death as meaningless, I’d also learned the importance of survival. Maybe that’s inconsistent, holding life and death void of meaning while valuing survival. All I know is it’s how I think and feel and live, so I don’t care.

I said I wouldn’t go into detail and I won’t. All I’ll say is that by the time Broker called me to the Quad Cities and tossed that airport business in my lap, I’d been doing free-lance work for him for five and a half years. And I did consider myself a free agent, even though I worked solely through Broker, since I had no doubt I could hook up with some other similar “booking agent” with no trouble. There were other Brokers around, though I didn’t know them by name. But, like Broker, they would crawl out of the plush woodwork somewhere and contact me if I wanted them to.

Some of what I did for Broker was undoubtedly mob- related, but only some of it. To the best of my knowledge Broker was not in the direct employ of the Family (or Outfit or Mafia or whatever) and did only piecework for them, assignments that were in some way inconvenient for handling through conventional Family channels. Only rarely would a hit of mine in one of the larger cities, like Chicago or Milwaukee, be mob-related, as the Family had enough help on the local payroll to handle practically anything; with the smaller-scale Family operations, in cities of less than half a million, outside help through the Broker or someone like him might be called upon. Other than that, the person who came to Broker was your run-of-the-mill, everyday average citizen who has three to seven thousand dollars handy to pay for killing someone he doesn’t like.

I had built up no particular philosophy about my work, but then I had no particular problem living with myself, so I didn’t really need one. I guess I did develop my own little handful of rationalizations to fall back on, should I need them some rainy day. One of them was that any person somebody wanted dead more than likely deserved it. But I knew that wasn’t necessarily true. A better rationalization was that this was just an extension of being a soldier and what I was doing was neither moral nor immoral, but amoral, like war.

Which is a good rationalization, but then you have to rationalize war.

What I realized at the outset as well as later was that certain people are going to want certain other people dead, and what are you going to do? Once somebody decides another somebody is going to have to die, that’s the ballgame. All that’s left are details.

Anybody I ever hit was set to go anyway. I saw to it that it happened fast and clean. It was something like working in a butcher shop, only my job pays better, the hours are shorter and there isn’t the mess.

5

* * *

* * *

EDDIE ROBINSON SAID, “Mother of Mercy, is this the end of Rico?” and somebody made a noise outside the motel room, out on the balcony. I eased the volume down on the television and listened: nothing for a moment, then whoever it was knocked at the sliding glass door.

I turned off the set and checked my watch. I’d been looking at the late late show, which was just getting over anyway, and it was

ten before two A.M. About right for Broker, though maybe a shade early; I’d expected him to show more like three-thirty or four, when it’d be extremely unlikely anybody’d be up and about to see him come calling.

The knocking continued, got insistent. I swigged down the last of the Coke and got up off the bed, set the empty on the dresser next to the three bottles I’d drained watching the old gangster picture, which wasn’t bad at all considering its age. That Robinson guy was a pro, you really had to respect him. But every fifteen minutes two clowns came on and pitched used cars for half an hour, and each time they came on I went out for a Coke. On my way to the door I opened my suitcase on the stand and got out the automatic and held it behind me.

I’d cleaned the gun and switched barrels on it since the afternoon; the silencer was on and clean, too.

I slid the door open a crack and the son of a bitch stuck his foot in and with it slid the glass panel hard open and came in fist-first, and it was a goddamn big fist, the mother of all fists, half-filling my face as it struck. My feet went out from under me and the automatic jumped out of my hand and tumbled under the bed—but the guy hadn’t even seen the gun. By the time he was in the door and getting his first look at me, I was on my ass.

My nose was bleeding, not broken but bleeding, and I was stunned. But I could see that the guy’s hands were empty, so I didn’t dive for the automatic under the bed. I wanted first to play the situation out, at least a few moment’s worth.

He was pretty big. Six-two, I’d say, which put him four inches over my head, and he was a solid two hundred pounds in a nicely cut tan business suit. He was around forty, or forty-five, with a college fraternity face set under iron-gray short-cropped hair that just missed being a butch. There were no lines on that face, not a one, except where his brow was crinkling over close-set gray eyes that peered out from behind—Christ, yes—dark-framed glasses. What the hell kind of material was Broker sending out, these days?

Scratch Fever

Scratch Fever Stolen Away

Stolen Away The Wrong Quarry (Hard Case Crime)

The Wrong Quarry (Hard Case Crime) Quarry

Quarry Hard Case Crime: Deadly Beloved

Hard Case Crime: Deadly Beloved Hush Money

Hush Money The Million-Dollar Wound

The Million-Dollar Wound Mourn The Living

Mourn The Living True Crime

True Crime Hard Cash

Hard Cash Triple Play: A Nathan Heller Casebook

Triple Play: A Nathan Heller Casebook Hard Case Crime: The First Quarry

Hard Case Crime: The First Quarry Spree

Spree Chicago Lightning : The Collected Nathan Heller Short Stories

Chicago Lightning : The Collected Nathan Heller Short Stories Fly Paper

Fly Paper Seduction of the Innocent (Hard Case Crime)

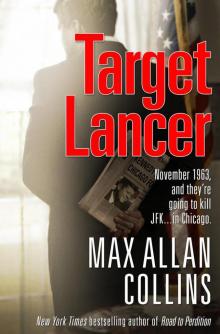

Seduction of the Innocent (Hard Case Crime) Target Lancer

Target Lancer