- Home

- Collins, Max Allan

Triple Play: A Nathan Heller Casebook Page 2

Triple Play: A Nathan Heller Casebook Read online

Page 2

“Sure,” I said. “I’ll be right there.”

He gave me the address (of his home), and I wrote it down and hung up; went out in the kitchen, where Peg sat in her white terry cloth bathrobe, staring over her black coffee.

“Can you fix yourself something, honey?” I asked. “I’m going to have to skip breakfast.”

Peg looked at me hollow-eyed.

“I want a divorce,” she said.

I swallowed. “Well, maybe I do have time to fix you a little breakfast.”

She looked at me hard. “I’m not kidding, Nate. I want a divorce.”

I nodded. Sighed, and said, “We’ll talk about it later.”

She looked away. Sipped her coffee. “Let’s do that,” she said.

I slipped on my suit coat and went out into the bright, sunny day. Birds were chirping. From down the street came the gentle whir of a lawn mower. It would be hot later, but right now it was pleasant, even a little cool.

The dark blue Plymouth was at the curb and I went to it. Well, maybe this wasn’t all bad: maybe this meant A-1’s business would be picking up, now that divorce had finally come home from the war.

2

The house—mansion, really—had been once belonged to a guy named Murphy who invented the bed of the same name, one of which I had slept in many a night, back when my office and my apartment were one and the same. But the rectangular cream-color brick building, wearing its jaunty green hat of a roof, had long ago been turned into a two-family dwelling.

Nonetheless, it was an impressive residence, with a sloping lawn and a twin-pillared entrance, just a block from the lake on the far North Side. And the Keenan family had a whole floor to themselves, the first, with seven spacious rooms. Bob Keenan was doing all right, with his OPA position.

Only right now he wasn’t doing so good.

He met me at the front door; in shirtsleeves, no tie, his fleshy face long and pale, eyes wide with worry. He was around forty, but something, this morning, had added an immediate extra ten years.

“Thank you, Nate,” he said, grasping my hand eagerly, “thank you for coming.”

“Sure, Bob,” I said.

He ushered me through the nicely but not lavishly furnished apartment like a guy with the flu showing a plumber where the busted toilet was.

“Look in here,” he said, and he held his palm out. I entered what was clearly a child’s room, a little girl’s room. Pink floral wallpaper, a graceful tiny wooden bed, slippers on the rug nearby, sheer feminine curtains, a toy chest on which various dolls sat like sweetly obedient children.

I shrugged. “What…?”

“This is JoAnn’s room,” he said, as if that explained it.

“Your little girl?”

He nodded. “The younger of my two girls. Jane’s with her mother in the kitchen.”

The bed was unmade; the window was open. Lake wind whispered in.

“Where’s JoAnn, Bob?” I asked.

“Gone,” he said. He swallowed thickly. “Look at this.”

He walked to the window; pointed to a scrap of paper on the floor. I walked there, knelt. I did not pick up the greasy scrap of foolscap. I didn’t have to, to read the crudely printed words there:

“Get $20,000 Ready & Waite for Word. Do Not Notify FBI or Police. Bills in 5’s and 10’s. Burn this for her safty!”

I stood and sucked in some air; hands on hips, I looked into Bob Keenan’s wide, red, desperate eyes and said, “You haven’t called the cops?”

“No. Or the FBI. I called you.”

Sounding more irritable than I meant to, I said, “For Christ’s sake, why?”

“The note said no police. I needed help. I may need an intermediary. I sure as hell need somebody who knows his way around this kind of thing.”

I gestured with open, raised palms, like a mime making a wall. “Don’t touch anything. Have you touched anything?”

“No. Not even the note.”

“Good. Good.” I put my hand on his shoulder. “Now, just take it easy, Bob. Let’s go sit in the living room.”

I walked him in there, hand never leaving his shoulder.

“Okay,” I said gently, “why exactly did you call me?”

He was next to me on the couch, sitting slumped, staring downward, legs apart, hands clasped. He was a big man—not fat: big.

He shrugged. “I knew you worked on the Lindbergh case.”

Yeah, and hadn’t that worked out swell.

“I was a cop, then,” I said. “I was the liaison between the Chicago PD and the New Jersey authorities. And that was a long time ago.”

“Well, Ken mentioned it once.”

“Did you call Ken before you called me? Did he suggest you call me?”

Ken was the attorney who was our mutual friend and business associate.

“No. Nate…to be quite frank with you, I called because, well…you’re supposed to be connected.”

I sighed. “I’ve had dealings with the Outfit from time to time, but I’m no gangster, Bob, and even if I was…”

“I didn’t mean that! If you were a gangster, do you think I would have called you?”

“I’m not understanding this, Bob.”

His wife, Norma, entered the room tentatively; she was a pretty, petite woman in a floral-print dress that was like a darker version of the wallpaper in her little girl’s room. Her pleasant features were distorted; there was a wildness in her face. She hadn’t cried yet. She was too upset.

I stood. If I’d ever felt more awkward, I couldn’t remember when.

“Is everything all right, Bob? Is this your detective friend?”

“Yes. This is Nate Heller.”

She came to me and gave me a skull-like smile. “Thank for you coming. Oh, thank you so much for coming. Can you help us?”

“Yes,” I said. It was the only thing I could say.

Relief filled her chest and filtered up through her face; but her eyes remained wild.

“Please go sit with Jane,” Bob said, patting her arm. He looked at me as if an explanation were necessary. “Jane and her little sister are so very close. She and JoAnn are only two years apart.”

I nodded, and the wife went hurriedly away, as if rushing to make sure Jane were still there.

We sat back down.

“I know you’ve had dealings with the mob,” Keenan said. “The problem is…so I have I. Or actually, the problem is, I haven’t.”

“Pardon?”

He sighed and shook his head. “I only moved here six months ago. I’d been second-in-command in the New York office. In Albany.”

“Of the OPA, you mean?”

“Yes,” he said, nodding. “I guess I don’t have to tell you the pressures a person in my position is under. We’re in charge of everything from building and industrial materials to meat to gasoline to…well. Anyway. I didn’t play ball with the mobsters out there. There were threats against me, against my family, but I didn’t take their money. I asked for a transfer. I was sent here.”

Chicago? That was a hell of a place to hide from mobsters.

He read the thought in my face.

“I know,” he said, raising an eyebrow, “but I wasn’t given a choice in the matter. Oddly, none of that type of people have contacted me here. But then, things are winding down…rationing’s all but a thing of the past.” He laughed mirthlessly. “That’s the irony. The sad goddamn irony.”

“What is?”

He was shaking his head. “The announcement will be made later this week: the OPA is out of business. They’re shutting us down. I’m moving over to a Department of Agriculture position.”

“I see.” I let out another sigh; it was that kind of situation. “So, because the note said not to notify the authorities, and because you’ve had threats from gangsters before, you called me in.”

I had my hands on my knees; he placed his hand over my nearest one, and squeezed. It was an earnest gesture, and embarrassed hell out of me.

“You’ve got to help us,” he said.

“I will. I will. I’ll be glad to serve as an intermediary, and I’ll be glad to advise you and do whatever you think will be useful.”

“Thank God,” he said.

“But first we call the cops.”

“What…?”

“Are you a gambling man, Bob?”

“Well, yes, I suppose, in a small way, but not with my daughter’s life, for God’s sake!”

“I know what the odds are in a case like this. In a case like this, children are recovered unharmed more frequently when the police and FBI are brought in.”

“But the note said…”

“How old is JoAnn?”

“She’s six.”

“That’s old enough for her to be able to describe her kidnappers. That’s old enough for her to pick them out of a lineup.”

“I don’t understand what you’re saying.”

“Bob.” And now I reached over and clasped his hand. He looked at me with haunted, watery eyes. “Kidnapping’s a federal offense, Bob. It’s a capital crime.”

He swallowed. “Then they’ll probably kill her, won’t they? If she isn’t dead already.”

“Your chances are better with the authorities in on it. We’ll work it from both ends: negotiate with the kidnappers, even as the cops are beating the bushes trying to find the bastards. And JoAnn.”

“If she’s not already dead,” he said.

I just looked at him. Then I nodded.

He began to weep.

I patted his back, gently. There there. There there.

3

The first cop to arrive was Detective Kruger from Summerdale District station; he was a stocky man in a rumpled suit with an equally rumpled face. His was the naturally mournful countenance of a hound. He looked a little more mournful than usual as he glanced around the child’s bedroom.

Keenan was tagging along, pointing things out. “That window,” he said, “I only had it open maybe five inches, last night, to let in the breeze. But now it’s wide open.”

Kruger nodded, taking it all in.

“And the bedcovers—JoAnn would never fold them back neatly like that.”

Kruger looked at Keenan with eyes that were sharp in the folds of his face. “You heard nothin’ unusual last night?”

Keenan flinched, almost as if embarrassed. “Well…my wife did.”

“Could I speak to her?”

“Not just yet. Not just yet.”

“Bob,” I said, prompting him, trying not to intrude on Kruger but wanting to be of help, “what did Norma hear?”

“She heard the neighbor’s dog barking—sometime after midnight. She sat up in bed, wide awake, thought she heard JoAnn’s voice. Went to JoAnn’s door, listened, didn’t hear anything…and went back to bed.”

Kruger nodded somberly.

“Please don’t ask her about it,” Keenan said. “She’s blaming herself.”

We all knew that was foolish of her; but we all also knew there was nothing to done about it.

The Scientific Crime Detection Laboratory team arrived, as did the photographer attached to Homicide, and soon the place was swarming with suits and ties. Kruger, who I knew a little, which was why I’d asked for him specifically when I called the Summerdale station, buttonholed me.

“Look, Heller,” he said pleasantly, brushing something off the shoulder of my suit coat. “I know you’re a good man, but there’s people on the force who think you smell.”

A long time ago, I had testified against a couple of crooked cops—crooked even by Chicago standards. By my standards, even. But cops, like crooks, weren’t supposed to rat each other out; and even fifteen years later that put me on a lot of shit lists.

“I’ll try to stay downwind,” I said.

“Good idea. When the feds show, they’re not going to relish havin’ a private eye on the scene, either.”

“I’m only here because Bob Keenan wants me.”

“I think he needs you here,” Kruger said, nodding, “for his peace of mind. Just stay on the sidelines.”

I nodded back.

Kruger had turned to move on, when as an afterthought he looked back and said, “Hey, uh—sorry about your pal Drury. That’s a goddamn shame.”

I’d worked with Bill Drury on the pickpocket detail back in the early ’30s; he was that rare Chicago animal: an honest cop. He also had an obsessive hatred for the Outfit, which had gotten him in trouble. He was currently on suspension. “Let that be a lesson to you,” I said cheerfully. “That’s what happens to cops who do their jobs.”

Kruger shrugged and shambled off, to oversee the forensic boys.

The day was a long one. The FBI arrived in all their officious glory; but they were efficient, putting a tape recorder on the phone, in case a ransom call should come in. Reporters got wind of the kidnapping, but outside the boys in blue roped off the area and were keeping them out for now—a crime lab team was making plaster impressions of footprints and probable ladder indentations under the bedroom window. A radio station crew was allowed to come in so Bob could record pleas to the kidnappers (“She’s just a little girl…please don’t hurt her…she was only wearing her pajamas, so wrap a blanket around her, please”). Beyond the fingerprinting and photos, the only real police work I witnessed was a brief interrogation of the maid of the family upstairs; a colored girl named Leona, she reported hearing JoAnn say, “I’m sleepy,” around half past midnight. Leona’s room was directly above the girl’s.

Kruger came over and sat on the couch next to me, around lunchtime. “Want to grab a bite somewhere, Heller?”

“Sure.”

He drove me to a corner café four blocks away and we sat at the counter. “We found a ladder,” he said. “In a backyard a few houses to the south of Keenan’s.”

“Yeah? Does it match the indentations in the ground?”

Kruger nodded.

“Any scratches on the bricks near the window?”

Kruger nodded again. “Matches those, too. Ladder was a little short.”

The first-floor window was seven and a half feet off the ground; the basement windows of the building were mostly exposed, in typical Chicago fashion.

“Funny thing,” Kruger said. “Ladder had a broken rung.”

“A broken rung? Jesus. Just like…” I cut myself off.

“Like the Lindbergh case,” Kruger said. “You worked that, didn’t you?”

“Yeah.”

“They killed that kid, didn’t they?”

“That’s the story.”

“This one’s dead, too, isn’t she?”

The waitress came and poured us coffee.

“Probably,” I said.

“Keenan thinks maybe the Outfit’s behind this,” Kruger said.

“I know he does.”

“What do you think, Heller?”

I laughed humorlessly. “Not in a million years. This is an amateur, and a stupid one.”

“Oh?”

“Who else would risk the hot seat for twenty grand?”

He considered that briefly. “You know, Heller—Keenan’s made some unpopular decisions on the OPA board.”

“Not unpopular enough to warrant something like this.”

“I suppose.” He was sugaring his coffee—overdoing it, now that sugar wasn’t so scarce. His hound-dog face studied the swirling coffee as his spoon churned it up. “How do you haul a kid out of her room in the middle of the night without causing a stir?”

“I can think of two ways.”

“Yeah?”

“It was somebody who knew her, and she went willingly, trustingly.”

“Yeah.”

“Or,” I said, “they killed her in bed, and carried her out like a sack of sugar.”

Kruger swallowed thickly; then he raised his coffee and sipped. “Yeah,” he said.

4

I left Kruger at the counter where he was working on a big slice of apple pie, and used a pay

phone to call home.

“Nate,” Peg said, before I’d had a chance to say anything, “don’t you know that fellow Keenan? Robert Keenan?”

“Yes,” I said.

“I just heard him on the radio,” she said. Her voice sounded both urgent and upset. “His daughter…”

“I know,” I said. “Bob Keenan is who called me this morning. He called me before he called the police.”

There was a pause. Then: “Are you working on the case?”

“Yes. Sort of. The cops and the FBI, it’s their baby.” Poor choice of words. I moved ahead quickly: “But Bob wants me around. In case an intermediary is needed or something.”

“Nate, you’ve got to help him. You’ve got to help him get his little girl back.”

This morning was forgotten. No talk of divorce now. Just a pregnant mother frightened by the radio, wanting some reassurance from her man. Wanting him to tell her that this glorious post-war world really was a wonderful, safe place to bring a child into.

“I’ll try, Peg. I’ll try. Don’t wait supper for me.”

That afternoon, a pair of plainclothes men gave Kruger a sobering report. They stayed out of Keenan’s earshot, but Kruger didn’t seem to mind my eavesdropping.

They—and several dozen more plainclothes dicks—had been combing the neighborhood, talking to neighbors and specifically to the janitors of the many apartment buildings in the area. One of these janitors had found something disturbing in his basement laundry room.

“Blood smears in a laundry tub,” a thin young detective told Kruger.

“And a storage locker that had been broken into,” his older, but just as skinny partner said. “Some shopping bags scattered around—and some rags that were stained, too. Reddish-brown stains.”

Kruger stared at the floor. “Let’s get a forensic team over there.”

The detectives nodded, and went off to do that.

Mrs. Keenan and ten-year-old Jane were upstairs, at the neighbors’, through all of this; but Bob stayed right there, at the phone, waiting for it to ring. It didn’t.

I stayed pretty close to him, though I circulated from time to time, picking up on what the detectives were saying. The mood was grim. I drank a lot of coffee, till I started feeling jumpy, then backed off.

Scratch Fever

Scratch Fever Stolen Away

Stolen Away The Wrong Quarry (Hard Case Crime)

The Wrong Quarry (Hard Case Crime) Quarry

Quarry Hard Case Crime: Deadly Beloved

Hard Case Crime: Deadly Beloved Hush Money

Hush Money The Million-Dollar Wound

The Million-Dollar Wound Mourn The Living

Mourn The Living True Crime

True Crime Hard Cash

Hard Cash Triple Play: A Nathan Heller Casebook

Triple Play: A Nathan Heller Casebook Hard Case Crime: The First Quarry

Hard Case Crime: The First Quarry Spree

Spree Chicago Lightning : The Collected Nathan Heller Short Stories

Chicago Lightning : The Collected Nathan Heller Short Stories Fly Paper

Fly Paper Seduction of the Innocent (Hard Case Crime)

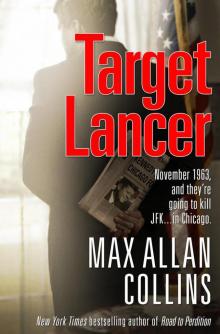

Seduction of the Innocent (Hard Case Crime) Target Lancer

Target Lancer