- Home

- Collins, Max Allan

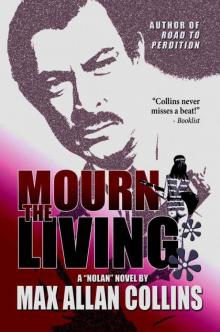

Mourn The Living Page 3

Mourn The Living Read online

Page 3

Tisor didn’t bother Nolan any more. Now that Nolan had his food and was eating, he wouldn’t like to be bothered.

Tisor sipped his coffee and thought about his cold, old friend. What balls the guy had! Nolan had some stones bucking odds like that. And the hell of it was, if he kept moving, Nolan just might be hard enough a character to beat the Boys at their own game.

When both had finished, they got up from the table, Nolan paid the check and Tisor tipped the waitress a quarter. The two men walked out into the raw night air and waited for an opening to jaywalk back across the highway to the motel.

Tisor stood with his hands in his jacket pockets, watching his breath smoke in the chill, while Nolan got his key out and opened the door to the cabin. Nolan did not invite Tisor in.

He said, “See you tomorrow, Sid.”

“Okay, Nolan . . . Nolan?”

“Yeah?”

“You mind if I ask you something else? Just one more thing, then I won’t ask you any more questions.”

Nolan shrugged.

“How much you made off the Boys so far?”

Nolan grinned the flat, humorless grin. “Don’t know for sure. It’s spread around, in banks. Maybe half a million. Maybe a little less.”

Tisor laughed. “Shee-it! How long you gonna keep this up?”

Nolan stepped inside the cabin. He said, “You said one more question, Sid, and you’ve had it. Goodnight.” He closed the door.

Tisor turned and headed for the Tempest. He got it started on the third try and wheeled out of the parking lot.

He knew damn well how long Nolan would play his little game with Charlie Franco.

Till one of them was dead.

4

WHEN TISOR got out of bed the next morning and went downstairs to make coffee, he found Nolan waiting for him in the living room. Nolan was sitting on the couch, dressed in a yellow short-sleeved button-down shirt and brown slacks. He was smoking a cigarette and looking at the centerfold in Sid’s latest Playboy, a photo of a nude girl smoking a cigar.

“Hi, Nolan.” Tisor tried to conceal his surprise.

Nolan said, “Good morning,” and tossed Tisor’s Playboy down on the table. “Nice tits, but what can you do with a picture?”

Tisor said, “When you’re my age, looking’s sometimes all there is.”

Nolan grunted.

“Want some coffee?”

“I started some when I got here. Ought to be done.”

“I’ll get it.” Tisor trudged into the kitchen, the tile floor cold to his bare feet. He never ceased to be amazed by Nolan. He wanted to ask Nolan how he got in—Tisor had the night before locked the house up tight—but he knew Nolan had no patience with curiosity.

Nolan had risen at 6:30, after eight hours of sleep, and had taken a cab to Tisor’s place. He’d sat down across the street on a bus stop bench to watch, hiding behind a newspaper. He saw that no one, outside of himself, was keeping an eye on Tisor’s house. And it didn’t look like anybody besides Tisor was staying there, either. Sid looked clean, but over a single doubt Nolan would have frisked his own mother, had she been alive. Nolan sat staring at Sid’s white two-story frame house, one of those boxes they churned out every hour on the hour in the fifties, and didn’t get up from the bench till Sid’s morning paper was delivered at 7:30. By 7:34 he had entered the house, through a basement window, and by 8:05 he’d searched every room, including the one Sid was sleeping in. Then, satisfied that Sid was clean, he had plopped down on the couch and started looking at the pictures in the November Playboy. At eight-thirty Sid came down in his green terry-cloth robe, looking like a corpse that had been goosed back to life.

Tisor brought Nolan a cup of coffee, black, and set a cup for himself on the table by Nolan. “Be back in a minute,” Tisor said, and Nolan was on his second cup by the time Tisor came back down the stairs, dressed in a Hawaiian-print sport-shirt and baggy gray slacks. Tisor sat down in a chair across from Nolan and sipped his cup of coffee, which was too strong for him though he tried not to let on, since Nolan had made it. Nolan nearly let a grin out: he got a kick out of Tisor, who had been the most unlikely big-time “gangster” he had ever known.

Tisor was Charlie Franco’s brother-in-law—his wife’s maiden name was Rose Ann Franco—and had lived off Rosie’s relatives since the day they were married. He had been fairly respectable before that, a CPA keeping books for several small firms and embezzling just a trifle; but his wife had insisted he take part in her brother’s “business.” It was quite painless for Tisor, who had switched to bookkeeper for the Family—he was an efficient, overpaid little wheel. And it was just like the world of business, all numbers in columns, and the closest he ever got to violence was the occasional Mickey Spillane novel he read.

He liked Nolan, who in spite of an apparent coldness seemed less an animal to Tisor than the rest of the gangsters playing businessman games. And in one of his rare moments of courage, Sid had taken a big chance hiding out Nolan when Nolan killed Tisor’s no-good brother-in-law, that swishy bastard Sam Franco.

Now Tisor was all alone. He’d been alone for two years now, since he’d sent his little girl Irene off to college at Chelsey University. Before Irene was born, there had been Rosie, his wife; and when he lost Rosie, there was Diane, till she found somebody younger and richer. And always Irene, a wild but sweet kid, ever devoted to her old man. Tisor shook his head and sipped at the bitter coffee. Now there was nobody. Except Tisor himself, a lonely old man too afraid to take his own life.

Nolan said, “I have the same problem.”

Tisor shook himself out of reverie. “What’s that?”

“The past. I think about it, too. It’s no good thinking about it.”

Tisor smiled. That was the most personal remark Nolan had ever made to him.

Nolan poured himself another cup of the steaming black coffee and said, “What happened to Irene?”

Tisor’s head lowered. “Suicide, they say.”

“They don’t know.”

“Not for certain. You see . . . she was on LSD.”

“Oh.”

“She was on top of a building, fell off. The cops say she took a nose dive . . .”

“Yeah. Since she was tripping, they figure maybe she thought she could fly.”

Tisor’s eyes pleaded with Nolan. “Look into it for me, Nolan. Find out did she jump, did she fall, did she get pushed. But find out.”

“What about the local law?”

“Hell,” Tisor said. “The Chelsey cops couldn’t find their dick in the dark.”

“That where she went to school? Chelsey?”

“That’s right, Nolan. Chelsey University at Chelsey, Illinois.”

“Damn, Sid, I didn’t want to come to Illinois for even a day, but here I am. Now you want me to hop over to Chelsey and play bloodhound for you.”

“Listen to me, Nolan, hear it out. . . .”

“Chelsey’s only eighty miles from Chicago, Sid.”

Tisor got guts for once. “Goddamn you, Nolan! Since when are you afraid of the Boys? Do you want to pay a debt you owe, or do you want to welsh on it?”

Nolan knew what Tisor said was the truth; he wasn’t afraid of the Boys—he just had better things to do than make like a gumshoe. But it was a debt he owed, and it needed paying.

He said, “Go on, Sid. Tell me about it.”

5

TISOR’S EYES turned hard and he leaned toward Nolan. “My Irene was a wild one, Nolan. She could’ve taken that LSD trip on her own. And if so, maybe she did try a Superman off that building. But there were some things going on in Chelsey that might have got her killed.”

“Like what?”

“She was home one weekend this summer and told me about this operation the Boys got going in Chelsey.”

“What did she know about the Boys?”

“Well, before she went to college I broke it to her about my connection with them, explained it all. She took it pretty good, but it mus

t’ve been a shock since I was always such a Puritan-type father. You know, not mean to her or anything, just old-fashioned.”

“Yeah. Tell me what she saw going on in Chelsey.” Nolan could see it would be a struggle getting the facts from Tisor; the guy would just keep reminiscing about the dead girl if Nolan let him.

“The Boys’ operation, yeah. Well, they’re selling everything from booze to pills to marijuana to LSD. All aimed at the college crowd.”

“Irene a customer?”

“She never said, one way or another. I really can’t imagine her taking drugs, but then, I’m her father, what do I know? Anyway, she knew about the Boys’ operation and their market. You see, there’s this hippie colony in Chelsey she’s got friends in. They number over five hundred and all live in the kind of slum section of town. It’s got some publicity, maybe you read about it.”

“I didn’t. But Illinois seems too far east for a hippie colony.”

“Why?”

Nolan lit a smoke. “Too cold. Communal living’s swell, free love and all that. Till you freeze your ass off.”

Tisor smiled, nodded. “You got a point. But these kids aren’t what you’d call real hippies, if there is such a thing. Not California-style, anyway. They’re rich kids, most of ’em, living off their parents’ dough. They don’t look so good in their beads and wilted flowers, and they don’t smell so good, either. But they got money. Money for food, for heat . . .”

“For LSD,” Nolan put in.

“And for LSD,” Tisor agreed.

“Irene, was she one of the ‘hippies’?”

“Borderline. She hung out with them, but she was putting seventy-five a month in an off-campus apartment she shared with a working girl named Vicki Trask. The Trask girl was laying out seventy-five a month, too.”

“Hippies don’t live in hundred-fifty buck apartments. Not ‘real’ ones.”

“Well, Irene and her roommate weren’t deep-dyed Chelsey hippies. But, like I said, even the most sincere ones are just leeches sucking money off their parents. Chelsey is a rich-kid school, you know.”

“You think the Boys got a good thing going for them, then? Got any ideas what they’re getting for one trip?”

An LSD trip took 100 micrograms of d-lysergic acid diethylamide tartrate and cost pennies to make. “I think they’re getting around eight or ten bucks a trip,” said Tisor.

Nolan scratched his as yet unshaven chin. “They’re not making much off that. Granted, there isn’t much money wrapped up in producing LSD. Any two-bit chemist with the materials and a vacuum pump can whip up a batch. But even a confirmed tripper only takes a trip or two a week.”

“It’s a big campus, Nolan. Almost ten thousand students.”

“Still, you can’t figure more than four hundred trips a week. That’s less than four grand coming in.”

“That isn’t so bad, Nolan.”

“Yeah, but that’s their big seller, isn’t it, LSD?”

“They’re selling booze, too, to the frat crowd. Most any kid on campus might use pep pills now and then. Big market for pot.”

“They selling any hard stuff?”

“Heroin, you mean?”

“Yeah.”

“Hell, no. Nolan. The Commission of families in New York’s got control over stuff like that. You know that. Anybody caught with a dope set-up is going to get their ass kicked hard unless the Commission’s okayed it.”

Nolan shook his head. “I don’t understand this. LSD. Nickels and dimes. Why are the Boys fooling around with it?”

“Nolan, they got other things going for ’em in Chelsey! They got gambling, they got a massage parlor, a strip joint or two . . .”

“Don’t bull me, Sid. Take the college out of Chelsey and there’s only seven thousand people left. The Family doesn’t mess with small-time operations unless there’s a reason. I know they can’t be pulling in even five thousand a week, before expenses.”

“Nolan, I. . .”

“You’re not telling the whole story, Sid.”

Tisor looked at the floor. He didn’t want to meet Nolan’s eyes, if he could help it. “George Franco’s running the Chelsey operation.”

Nolan’s laugh was short, harsh. No wonder the set-up was small-time! An LSD ring, what a joke. You could save all the money you’d make off a racket like that and go to Riverview Park once a year.

“Sid,” Nolan said, “you and I both know what George Franco is.”

George Franco was the younger brother of Charlie Franco and the late Sam Franco, and also of Tisor’s late wife, Rosie. George: the obese, incompetent younger brother who couldn’t cut it and got sent places where he wouldn’t cause trouble. A glutton, a coward, and simple-minded to boot.

“Okay,” Sid admitted, “it’s no big set-up. It’s a small operation that Charlie gave George to give him something to do.”

Nolan got up from the couch. “Be seeing you, Sid.”

“Wait, Nolan, will you wait just a minute!”

“Having George Franco on hand makes this too close to home where the Boys are concerned, and at the same time makes any possible score small potatoes. Be seeing you.”

“Listen to me, will you just listen? It’s better than you think. George doesn’t have full charge, he’s more or less a figurehead. There’s a financial secretary, of sorts, who really runs the show. I don’t know the guy’s name, but he’s no dummy.”

“Where do you get your information?”

“George is my brother-in-law, remember?”

“Does he know Irene’s related?”

“He might have met her when she was a kid, but he doesn’t know I have . . . had a girl who went to Chelsey. At least as far as I know he doesn’t. That dumb asshole doesn’t know much of anything.”

“I’ll grant you that, Sid.”

“Look, George talked to me on the phone last week, social call, you know? I pumped him a little. They’re pulling in at least six grand a week.”

“Sid, it’s my life you’re trading bubblegum cards against.”

“Don’t forget you owe me, Nolan, remember that! And there’s going to be close to forty thousand in it for you, I swear.”

“At six grand a week, how do you figure? The Boys send in a bagman every Wednesday and take the last week’s earnings back to Chicago. That’s s.o.p. with the Family. I know these set-ups, Sid.”

“But they don’t come in weekly! Chelsey is so close to Chicago they don’t bother sending a man every week.”

“How often do they pick it up?”

“Every six weeks. But I don’t know where they keep it till then.”

“How about the local bank?”

“Nope, I checked it. They must keep it on ice somewhere.”

“So there ought to be around forty thousand in this for me, Sid, that right?”

“I think so, Nolan. Maybe more.”

Nolan thought for a moment. Then: “What makes you think this operation in Chelsey has anything to do with your daughter’s death?”

“Damn it, Nolan, I figure if they didn’t do anything outside of sell that cube of LSD she’s supposed to have swallowed, then they killed her, didn’t they? Besides, because she was my kid she knew things about the Boys and the connection they had to Chelsey. If she let any of that slip to the wrong person, it could have got her killed. And . . .” Tisor’s eyes were filmed over and he looked down at his hands, folded tightly in his lap.

“And what?”

“Nolan, I have to know why she died. I have to know.”

“It’s enough she’s dead, Sid.”

“No, it isn’t! She was the only thing I had to show for my entire life, she was the only thing I had left to care about! I’m not like you, Nolan . . . I can’t let go of something that important with a shrug.”

There were a few moments of silence, while Tisor regained a modicum of control. Nolan sat and seemed to be studying the thin ropes of smoke coiling off his cigarette.

“If I find out Irene

was murdered,” Nolan said, his voice a low, soft monotone, “and I find the one who did it, what am I supposed to do?”

“That’s up to you, Nolan.”

“You expect me to kill somebody?”

“I know you, Nolan. I expect if anyone needs killing, you’ll take care of it.”

“I’m not making any promises, you understand.”

“I understand, Nolan.”

“All right, then. Get some paper and write down every speck of information you got on Irene and Chelsey. The college, her friends, the Boys’ operation, George, everything you know about it. And put in a recent snap of Irene.”

“Right.” Tisor got a notebook and a pen and Nolan smoked two cigarettes while Tisor filled up three pages for him. Tisor gave Nolan the notebook, then went to a drawer to find a picture of his daughter.

“Here she is,” he said, holding a smudged Polaroid shot.

“That’s old, Sid—nothing newer? This is what she looked like when I knew her.”

“She got prettier in the last couple years since you saw her. I had her nose fixed, did you know that?”

“No.” She’d been a dark-haired girl, beautiful but for a nose that could have opened bottles, and it was nice that Sid had got it bobbed for her, but Nolan hardly saw it worth talking about when she was dead.

Tisor’s eyes were cloudy. “They . . . they told me on the phone that . . . she . . . she fell ten stories . . . it was awful. They sent her body back on a train for the . . . funeral. I had to have them keep the casket closed. . . .”

“Don’t waste your tears on the dead, Sid,” Nolan told him. “You got to mourn somebody, mourn the living—they got it tougher.”

“You . . . you don’t understand how it is . . .”

Hell, Nolan thought, dust doesn’t give a damn. But he said, “Sure, Sid, sure.”

“Let me tell you about her, Nolan . . .”

“I got to be going now, Sid.”

Scratch Fever

Scratch Fever Stolen Away

Stolen Away The Wrong Quarry (Hard Case Crime)

The Wrong Quarry (Hard Case Crime) Quarry

Quarry Hard Case Crime: Deadly Beloved

Hard Case Crime: Deadly Beloved Hush Money

Hush Money The Million-Dollar Wound

The Million-Dollar Wound Mourn The Living

Mourn The Living True Crime

True Crime Hard Cash

Hard Cash Triple Play: A Nathan Heller Casebook

Triple Play: A Nathan Heller Casebook Hard Case Crime: The First Quarry

Hard Case Crime: The First Quarry Spree

Spree Chicago Lightning : The Collected Nathan Heller Short Stories

Chicago Lightning : The Collected Nathan Heller Short Stories Fly Paper

Fly Paper Seduction of the Innocent (Hard Case Crime)

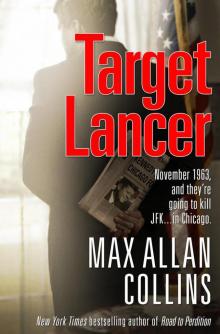

Seduction of the Innocent (Hard Case Crime) Target Lancer

Target Lancer